Resister in Sanctuary: We Won't Go

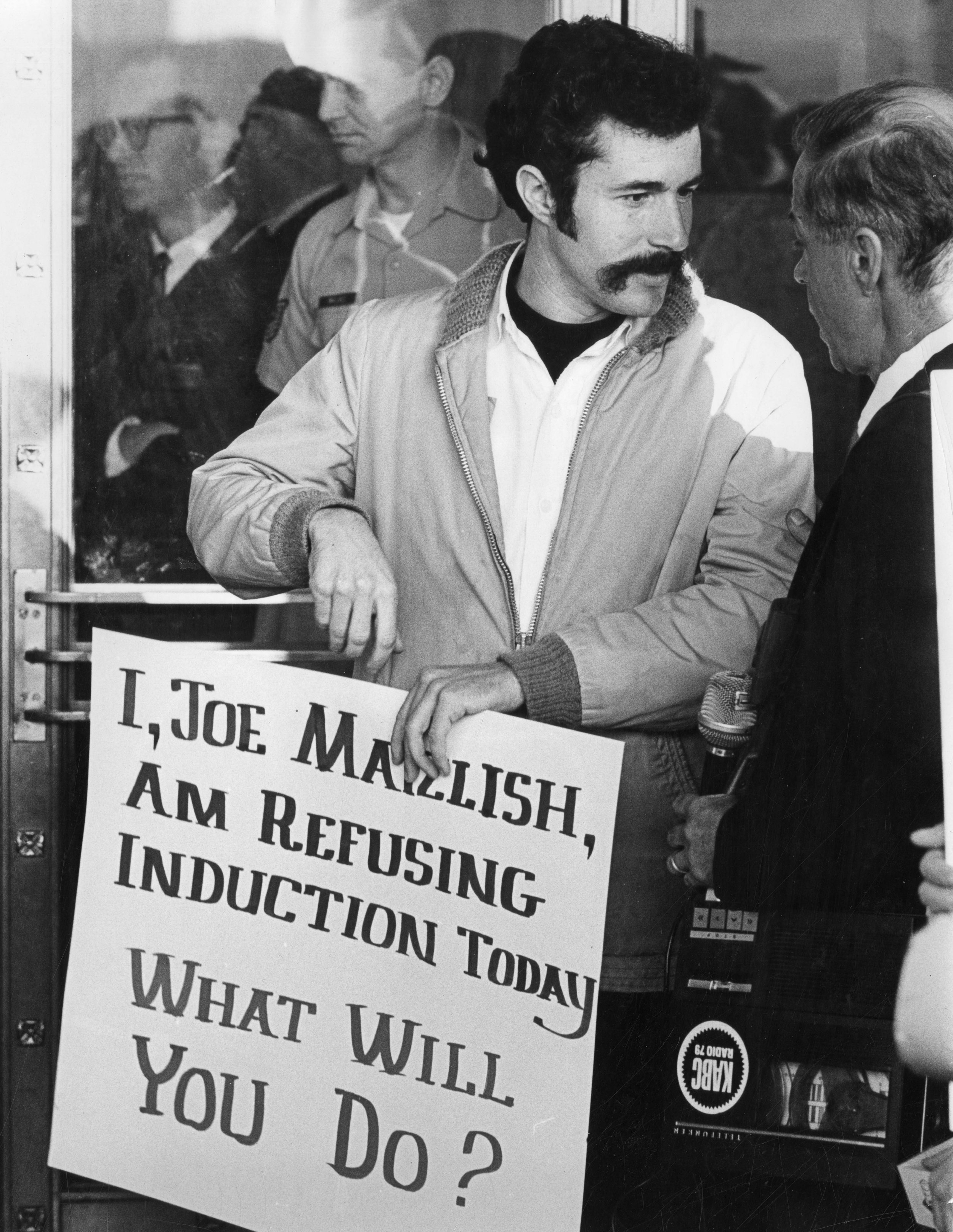

Image: Joe Maizlish at Induction Refusal, 1968, Black and white photograph. L.A. Resistance Collection, Los Angeles Public Library

In one glass case, what first draws my eye is a REMEMBER JOE MAIZLISH bumper sticker identical to the one I affixed to the bumper of my dad’s Ford Mustang in 1968. Yes, I do remember Joe Maizlish. Decades ago, I wrote to him in while he was in federal prison, where he served two and a half years of a three- sentence for refusing induction to the draft. Joe, now a psychologist and mediator, in present-day, is my neighbor in Silverlake.The item, along with posters in fonts of various degrees of psychedelia, is on exhibit at WE WON’T GO: The L.A. Resistance, Vietnam and the Draft (at the Central Library’s Getty Gallery until August 19).

Curated by Winter Karen Dellenbach, an L.A. Resister, together with Ani Boyadjian, Research & Special Collections Manager for the Los Angeles Public Library, this inspiring display of civil disobedience was drawn from the Los Angeles Resistance Archives, acquired by the library in 2014. The collection includes letters, posters still and moving images, diaries, mimeographed newsletters, draft cards and other ephemera donated by members of the L.A. Resistance and their supporters. Essentially, this is a chronicle of the non-violent anti-draft activities of the L.A. chapter of the Resistance, a nationwide movement.I recognize a black and white photo of General Hershey Bar, with his signature plastic B-52’s worn as medals. The real General Hershey, a Nixon advisor, was head of the Selective Service, and General Hershey Bar was a familiar sight at anti-war rallies in the ’60s. “Fixin-to-Die Rag” (Country Joe and the Fish) cues in my head:“Well, come on all of you big strong menUncle Sam needs your help againGot himself in a terrible jamWay down yonder in VietnamPut down your books and pick up a gunWe’re going to have a whole lot of fun”

But what sends my memory into overdrive is RESISTER IN SANCTUARY, in bold black letters across a legal size flyer. It’s a manifesto written by Gregory Nelson, then nineteen years old and briefly my high school sweetheart. Greg had openly refused to register a year earlier, as required by law, when he turned eighteen. In the fall of 1968, he asked the minister and congregation of Grace Episcopal Church in South Los Angeles to grant him sanctuary, a medieval tradition, for an act of conscience. His language is simple and direct:This is a period of deep disunity in our country.One source of that disunity is the war in Vietnam. I have refused to participate in that war—even to the degree of refusing to register for the draft. Now I am charged with a crime for that refusal. I feel that my refusal is an action consistent with the moral precepts and teachings of my society, an action directed toward ending the present war and healing the wounds of discord. I ask you, a visible guardian of our moral teachings and a main source of guidance to the people of our society, to consider my plea…

I was a junior in high school when I met Greg spring of 1968, through my volunteer work for the Resistance. I’d trade my pastel shirtwaist school uniform and saddle shoes for jeans, denim work shirt, jeans and sandals — then hurry down to the Resistance office in the red brick colonial on Westwood Blvd. There were a few other high-schoolers, but most of the supporters working there were college-aged. They impressed me as energized, purposeful and very cool. Lives were on the line.I’d join them in stuffing envelopes, or we’d pile into someone’s VW bug and head off to a local draft board with a pile of leaflets, trying to interest those young men who’d arrived for a draft physical in alternative actions, draft counseling. It was my first taste of communal activism and I cherished the palpable sense of “family” among those who planned to take a stand of conscience and those who supported them.Many Resisters were galvanized after hearing David Harris, the charismatic anti-draft activist and former Stanford student body president (then married to Joan Baez), speak about non-violent non-participation as a way to end the Vietnam War. I’d heard Harris at the Stanford campus, the summer I attended Junior Statesman Summer School there. His was a voice of persuasive moral passion, drawing from the ideas of Thoreau, Gandhi, and King, and Mario Savio. Harris called for young men to resist the draft openly and be willing to take the consequences, that “The way to do is to be.”I hung out with Greg early that summer of 1968.

It was the summer after the assassination of MLK in April at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. It was the summer after the assassination of RFK in L.A at the Ambassador Hotel in June the night of the California Primary. It was the summer before Nixon was elected president. The casualty count in Vietnam was rising and the government’s need for more bodies to feed the “Buzz Saw of War,” to use my dad’s phrase from WW2 — seemed insatiable.It was also a summer for young lovers to lie entwined under an Indian-print bedspread in a darkened studio apartment near the Venice Boardwalk, to listen to Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds twelve times and not care that the needle was sticking; to make midnight runs to Tomy’s Burgers on Ramparts; to dance wildly to the Jefferson Airplane at the Cheetah nightclub on the Pacific Ocean Park pier.… Since I cannot turn to the courts for justice, I turn to the church. I ask you to lend your church for a role that churches once played. I ask you to grant me sanctuary.Nelson’s plea was granted by Grace Episcopal Church on W. 78th Street in South Los Angeles.

On the day Nelson and his supporters gathered in the church, one of the Episcopal priests, Reverend Harlan Weitzel, was joined to Greg with a length of chain. In my journal from that day, October 2, 1968, I noted that it was Yom Kippur, that the bitter taste in my mouth was less from fasting than from fear and distress.Resistance founder David Harris was there to speak, to support Greg, and to lift our spirits. Greg said, ‘you sure rap well, Dave, who then yelled amen! Amen! And urged us all to sing’ Two young men burned their draft cards that day, I remember the packed crowd of supporters — including many of those whose papers are now in the archives at LAPL. I didn’t remember, until I read the notes to the exhibition, that Michelangelo Antonioni, the Italian film director, was in attendance that day as well, which made some kind of surreal sense. Oh, of course he was.

……..

In a letter to Joe Maizlish in prison, I described feeling hysterical when I learned what Greg was going to do, and how another, older Resister, helped to calm me. “I stood next to Greg’s mother in front of the church,” I wrote Joe. “… we were passing out flowers. The church was surrounded by federal marshals and police and Greg’s mother wondered aloud, ‘Why all these men for my one small boy who hasn’t even a comb in his pocket?’”

No one who was there will ever forget the approach of the U.S. marshals with their ridiculously over-sized bolt cutters, how they hesitated before approaching the dais, stepping over and even on bodies — to where the slight long-haired young man was chained to his friends and supporters. “I saw Greg, his bright eyes stare the marshal in the face and he said, I will go don’t hurt anybody please. And they still dragged him. They cut the chains and took Greg away and crammed him into a waiting car.”On a video clip playing on the wall of the Getty Gallery, a grey-bearded Greg Nelson — 50 years later — recalls how the chains were actually so loose he could have slipped out of them; that the church had been locked that day and he’d had to sneak in, in order to get arrested — a fact the uniformed Marshals found amusing.“

Each draft card turn-in was performance art, each refusal to register a brazen repudiation of coercion,” wrote Winter Dellenbach. “It was so much fun, and it was deadly serious, and it had deep consequences.”The scene in the sanctuary though, was not child’s play, not performance art, it was high drama: the chains; the supporters singing under the cross; the representatives of the State with their weapons; the violated sanctuary; the palpable communal determination to resist.Greg’s trial was on Friday, Oct 4th, at the downtown Federal Courthouse. When I arrived, I was surprised to see so many reporters. I assumed they were there for Greg. In fact they were covering the more sensational hearing for Sirhan Sirhan, who’d fired the shots that killed Robert Kennedy.

Greg represented himself at trial. “All the prosecutor had to do was to prove Greg was 18,” I wrote to Joe Maizlish at Safford Prison:“…That he hadn’t registered. That he lived at 1018 Pacific St. in Santa Monica. Greg didn’t present a defense, but he cross-examined the witnesses:-His high school vice-principal who testified Greg had indeed gone to Santa Monica High. Greg started lacing into him for making him salute the flag. (Later the judge said he couldn’t blame anyone for getting a chance to get back at their high school Vice Principal. )-His father, to testify he’d been born.-The draft board lady — to testify she had not received his registration. (Might you have lost it? asked Greg.)-The FBI agent who had warned Greg of the consequences of his action a year ago.The prosecutor was moved by Greg’s muteness on his defense. So was the judge. Greg made one statement — which the judge allowed — on the draft and the selective service system. Quite a natural, down-to-earth speech. And that was it. He was sentenced the same day and when led away said ‘I’ll say hello to Joe for you all.’”

……..

In conjunction with the exhibit, the library hosted a panel discussion on July 19th with three Los Angeles resisters — Geoff Fishman, Paul Barnes Lake, and Joe Maizlish. All served time in prison. Historian Jon Wiener, host of The Nation podcast, was the interlocutor.Wiener asked them each why they’d chosen to refuse the draft, what they experienced in prison, how it impacted the trajectory of their lives. How did they make their initial decision to resist?Geoff Fishman described how, when he was already at the induction center , waiting to be “processed” for the draft, there came a “moment of truth”:“When all were asked to acknowledge allegiance and acceptance into the army, to step forward to accept, I surprised myself. Everyone stepped forward except me.”

Joe Maizlish’s decision came in stages, the first revelation in 1965: “I was crossing a street in Berkeley with my brother. We looked at each other and said, ‘There’s no way we’re ever going to be in this war.” Three years later, he became “completely unable” to send in the form to renew his UCLA graduate student deferment, that “political free ticket,” as Dave Harris termed it, knowing others would be drafted to serve in his stead. “It wasn’t an actual decision,” he said, “it was my whole being — I can’t do this.”

As it was for Joe 50 years ago, our whole beings tell us that children shouldn’t be separated from parents, our whole beings tell us that asylum seekers should not be sent back to their deaths, that torture is wrong, that the earth itself is worth saving and fighting for.In these treacherous times of eroding civil liberties and rising authoritarianism, the L.A. Resistance Archive can serve as blueprint to help guide and inspire us. Exhibition co-curator Ani Boyadjian aptly summed up the enduring value of the collection: “It’s the intensity and passion of doing the right thing and it is a thing of beauty.”So thank you, Greg Nelson and Joe Maizlish and Paul Barnes Lake and Geoff Fishman and all the other Resisters who were willing to give up so much to take a stand against America’s immoral war in Vietnam. And, thanks to the Los Angeles Public Library, for preserving these stories for future generations — who will face such difficult decisions of their own.