Swans in the Morning: My Japanese Translator

April 15, 2025

I was lucky to be paired with a wonderful Japanese translator, Masako Hayakwa, on a trip to Japan in 1995, when I was on my quest to return a Japanese flag to the family of a Japanese soldier.

With Masako on the bus to Suibara from Niigata… [photo: L. Hamrol]

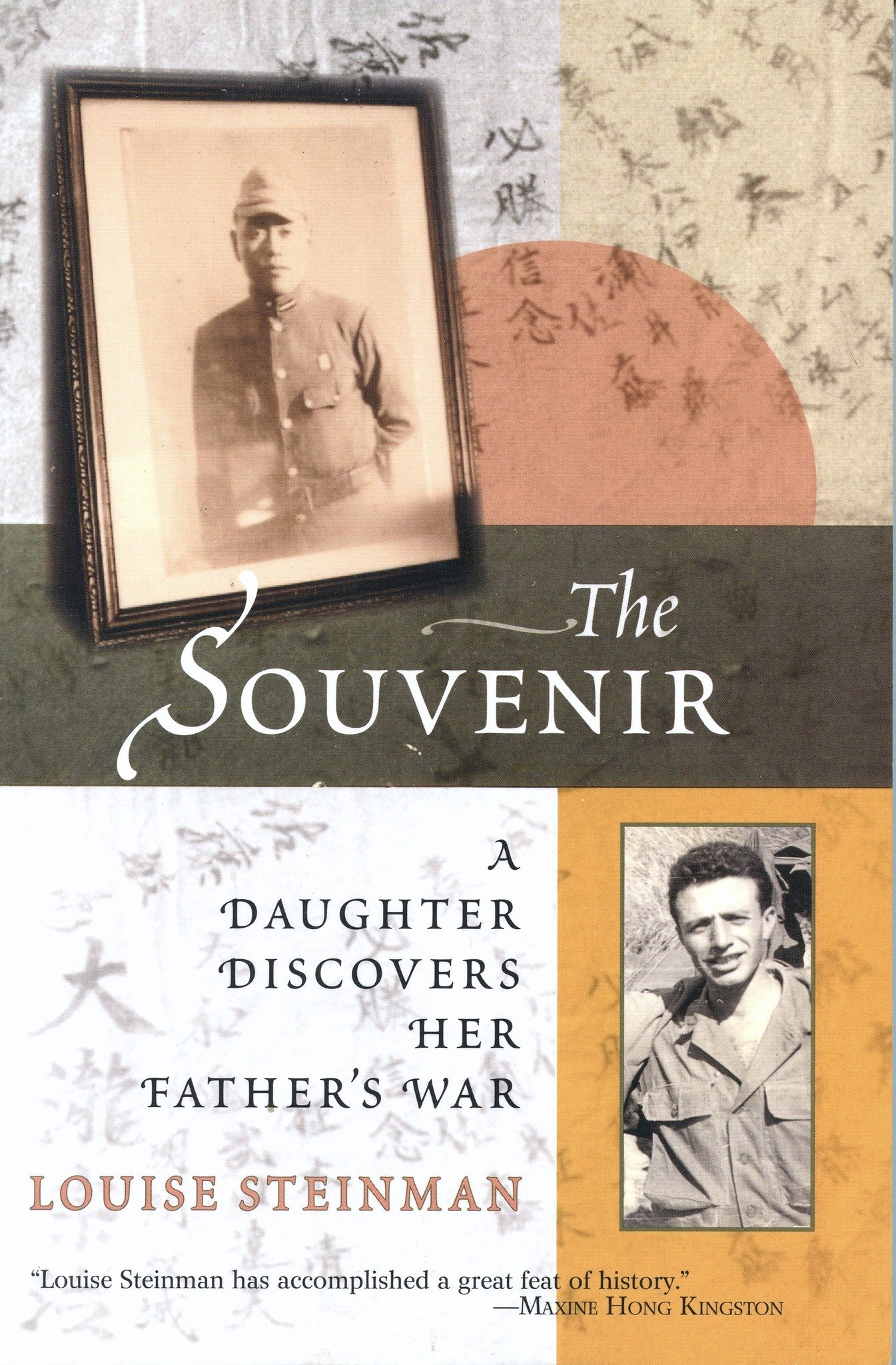

I discovered this square of frayed white silk folded in eighths— an orange-red disc in its center—in 1990, the year both my parents passed away. While cleaning out my parents’ condo in Culver City; I found the flag in a storage locker, inside a rusted metal ammo box which contained hundreds of yellowing letters my father wrote home to my mother during the Pacific War. My father regretted sending that souvenir to my mother. He apologized to her numerous times: “it was the worst thing I did in the war.”

I eventually asked a Japanese acquaintance, an artist named Rika Ohara to translate the Japanese characters brushed across the flag. “This is a good-luck banner, given to a Japanese soldier when he goes into battle. Perhaps when he leaves for duty overseas. It says here: To Yoshio Shimizu in the Great East Asian War. When You Persevere: You Win. The other characters on the flag are names.”

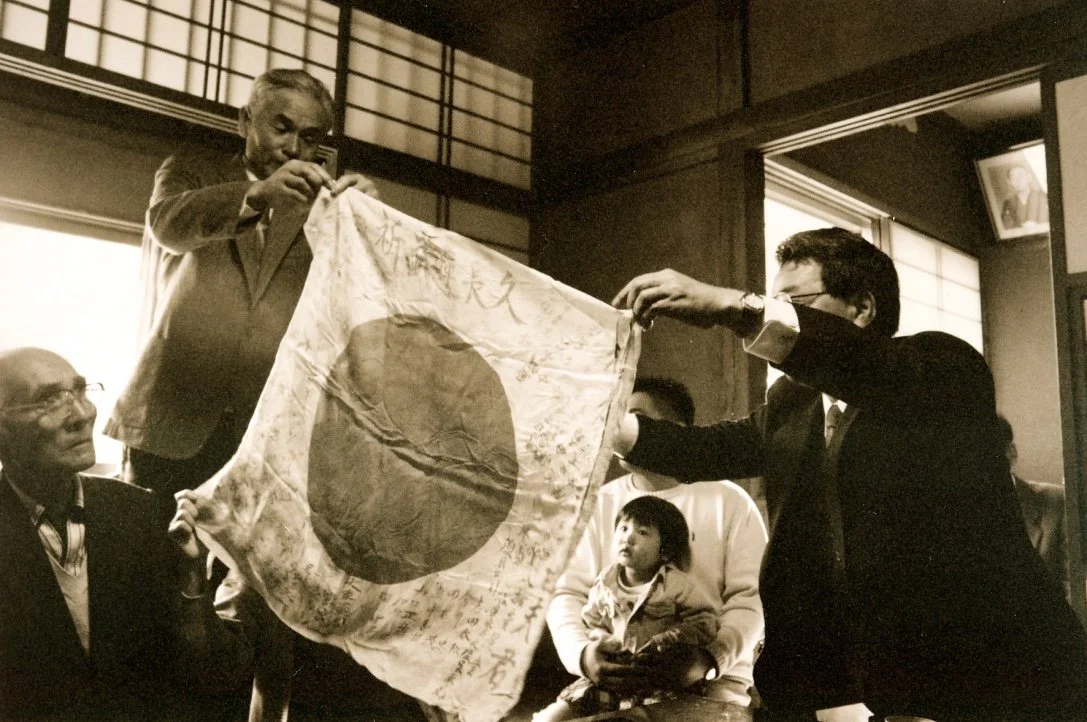

The flag of Yoshio Shimizu

After a full year of official (pre-computer) research, the Office of Records Research in the Social Welfare and War Victims Relief Bureau in the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare was able to track down surviving family of the soldier in the tiny town of Suibara, in Japan’s snow country. And to my good fortune, the extended Shimizu family welcomed my visit.

Me, Lloyd, Masako with the Shimizu family and Yoshio’s school friends Suibara, April 15, 1995

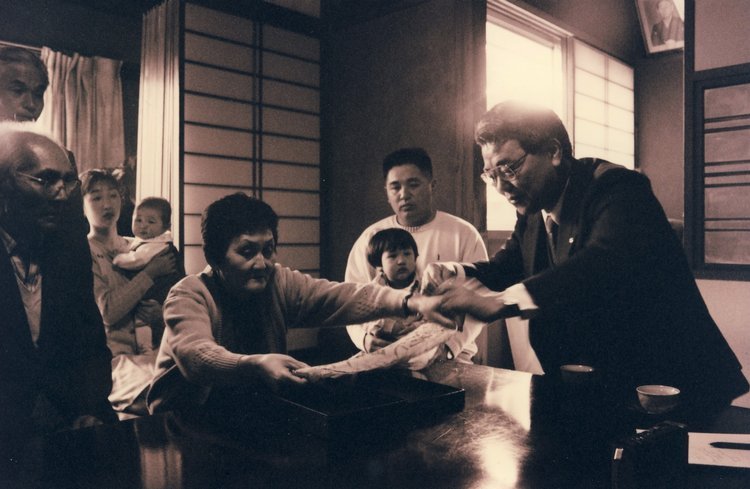

Masako was beside me, translating, when my husband and I gathered in Suibara with the mayor, some fifty or so people from the neighborhood (some of whom had signed Yoshio’s flag when he’d gone off to war) and several generations of the Shimizu family jammed into the living room of their house. As soon as I stepped inside noticed a simple altar with a framed black-and-white photograph of a young soldier, Yoshio Shimizu, his face plump and unlined.

photo: Lloyd Hamrol

Yoshio was eighteen when he was drafted, twenty-three when his family received word he had died. Yoshio “was a very gentle and kind person,” one of his boyhood friends told the room. Yoshio died in the Battle of Balete Pass, in Luzon, the Philippines. It was the same brutal campaign in the rugged Caraballo Mountains—one hundred and sixty-five consecutive days of combat—that my father endured as a soldier with the 25th U.S. Infantry Division. After introductions and speeches, I handed Hiroshi Shimizu the box. She drew out the flag with her gnarled hands and a collective gasp escaped in the room. Then crying. Then applause. Hiroshi’s husband, Suezo, asked to speak. Masako translated: “You have brought us back Yoshio. The government only sent sand in a box.”

Hiroshi Shimizu receives her brother’s flag [photo: Lloyd Hamrol]

return of the flag. [ photo: Lloyd Hamrol]

Everyone I met in Japan of a certain age had their war stories. On my second trip to Suibara, in 1998, with Masako’s help again, I interviewed several Suibara villagers. In most cases, my interviewees had never spoken of these war experiences; they were too painful. Young people I spoke to in Japan at that time knew little about their elders’ experiences in the war. I interviewed Mr. Abe, then eighty-four, a former hospital administrator who’d spent four years in a Siberian prison camp after just one week of active service in Korea—four years of bitter cold hard labor, which visibly pained him to recall. I listened to Mrs. Nakayama, an eighty-eight year old former second grade teacher whose husband, Takeo was drafted October 1, 1943, and died December 29th that same year in Java. She only learned of his death two years later. “When he died, I had two children and my mother-in-law to care for. I had a teaching job. We had to eat potato leaves, potato stems.” I learned how, during World War II, the military siphoned off Suibara’s agricultural bounty. The storerooms of rice, the barrels of miso and the mounds of huge green cabbages, the bushels of white daikon—all were requisitioned. “We had to give all the rice harvest to the government, even though we had nothing.” The people of Suibara ate tree bark and foraged in the mountains for wild greens. “You saw how a person could ‘grow thin like a mantis.’”

On that same reporting trip, in deep winter in the snow country, I witnessed the thrilling sight of the Siberian swans that return each season to Suibara’s Lake Hyoko. It’s the town’s main claim to fame, and the townspeople consider the birds “honored guests”; hunting them is strictly forbidden. It was not always so: it took a farmer named Junsaburo Yoshikawa, who in 1950, noted the appearance of ten whoopers on the lake after an absence of some four decades. He dedicated his life to encouraging the whoopers to stay, hacking through the ice on freezing mornings. He persuaded the villagers not to hunt them for food, to leave them in peace. Junzaburo was known as the Swan Father. (He was originally known of as “The Swan Fool.”) His wife was known as the Swan Widow. His son, Shigeo, who took over the responsibilities of feeding the birds after his father passed away, was known as the Swan Uncle. (The person who feeds the swan daily now is known as “Mr. Swan.”) Today Lake Hyoko is officially a protected zone, the “Winter Habitat of Wild Swans at Suibara.”

Swans at Lake Hyoko, Suibara, Japan

I loved venturing outside the Rhythm Inn (sic) in predawn darkness, down an snow-covered road in the direction of the mountains, past fine old two-story farmhouses with blue-tiled roofs. From the nearby lake, I could hear the morning greetings of thousands of whooper swans, sounding like a hundred orchestras tuning up simultaneously in the same concert hall. Sunlight leaked over the nearby Ide mountain range as the mighty five-foot-tall birds began their take-off, actually “running” on the water to gain enough speed to lift off.

After a week’s stay in Suibara, Masako invited me for an overnight at her home in Nagaoka. I met her very charming and hospitable husband, Norio Hayakawa, a professor of civil engineering at Nagaoka University of Technology. Norio, I learned, had been born in Manchuria, where his father, a civil engineer, had been posted by the Japanese government. After Japan’s defeat, Norio and his mother went on the run from Russian troops. While waiting for a ship to return them to Japan, his mother died of cholera. Six year-old Norio, malnourished, returned to Japan with his mother’s ashes in his backpack. He was raised by an uncle and aunt. His father remained a prisoner of war in Stalin’s Russia. When I first met Norio, and asked him about his father, he told me he didn’t want to talk about that part of his life. After dinner, however, he went to get a photo album out of the back bedroom. I listened to his quiet voice. I didn’t ask him to repeat anything. That night, after he told me his story, I lay there under the quilt in the tatami room unable to sleep.

I got up in the dark and went into the livingroom where he had left a photo from the album on the coffee table. I turned on the light to get a better look, marveled at the movie star handsomeness of his parents—his father in a jacket and tie, crisp white shirt, parted hair, glasses. his young lovely mother in a silk kimono jacket, holding her first and only child. Norio had tried to find his father’s grave in Siberia, through a forest across a frozen river, by foot, by tank, by truck, by boat. to the village that wasn’t there anymore and finally, to three holes in the ground which he was given to understand contained the remains of his father. “It is hard to believe such strange things can happen in one’s life,” he said, as if still trying to convince himself.

It's been exactly thirty years today, April 15th, since that momentous afternoon when I returned Yoshio’s flag to the Shimizu family, Masako at my side. She and I have stayed in touch over the decades. She updates me on the number of Siberian swans that winter-over in Suibara (recently more than nine thousand). She informed me when gentle Suezo Shimizu, Yoshio’s brother-in-law, passed away, and when her twelve year old granddaughter visited from Tokyo. She wrote after the disastrous tsunami in Fukushima.

And she wrote when her dear Norio passed away. That particular letter ended: “On the morning of Norio’s funeral, a flock of swans flew in a V over our house, which was unusual, unlike in Suibara where the swan lake is. Swans migrate from Siberia to Japan in winter. I believe that Norio’s father entrusted the swans to guide Norio to heaven where he is.”